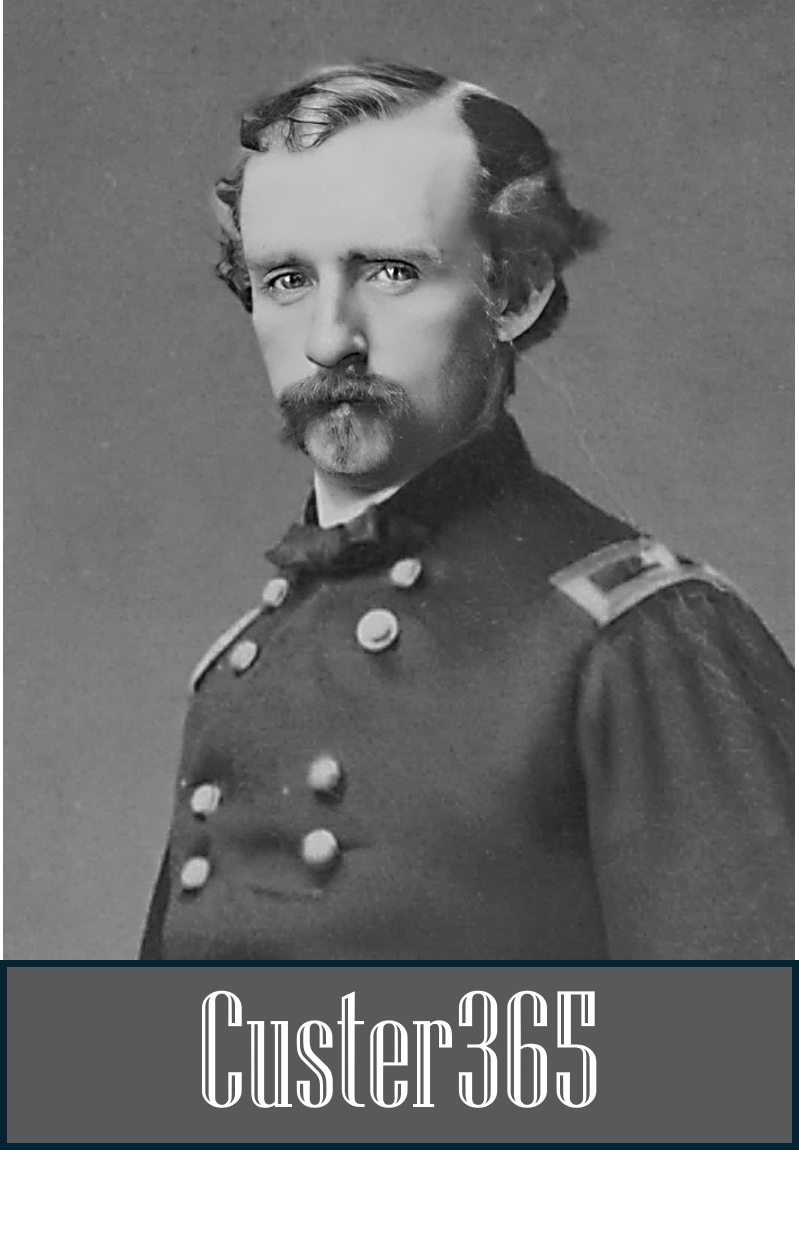

AUG 23: Custer Expedition Heads Home

On Aug. 23, 1874, Lt. Colonel George Custer’s Black Hills Expedition crosses back into Dakota Territory after exiting the Black Hills and turning east toward Bismarck and its home base of Fort Lincoln.

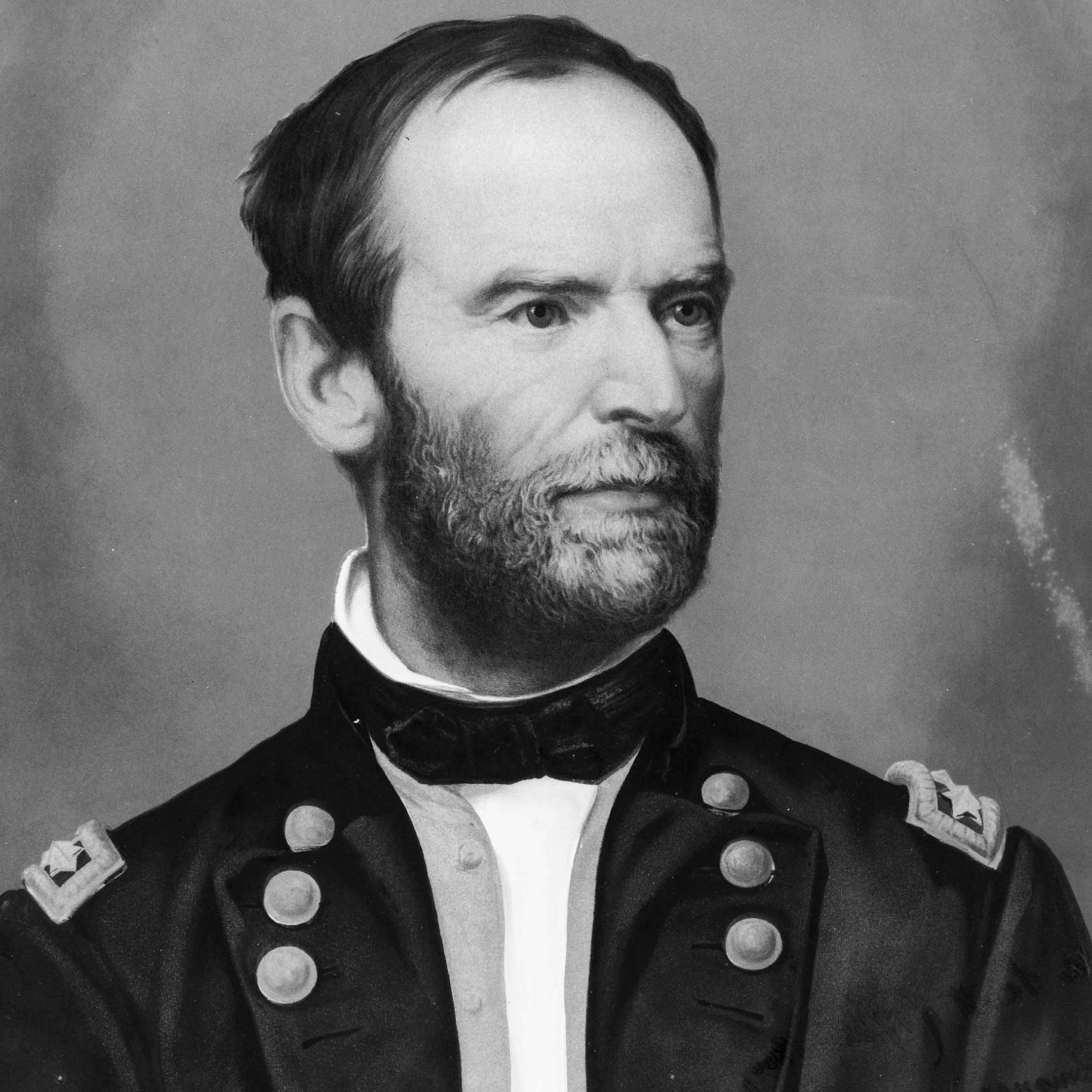

Commanding General of the U.S. Army William T. Sherman. (Credit: Library of Congress)

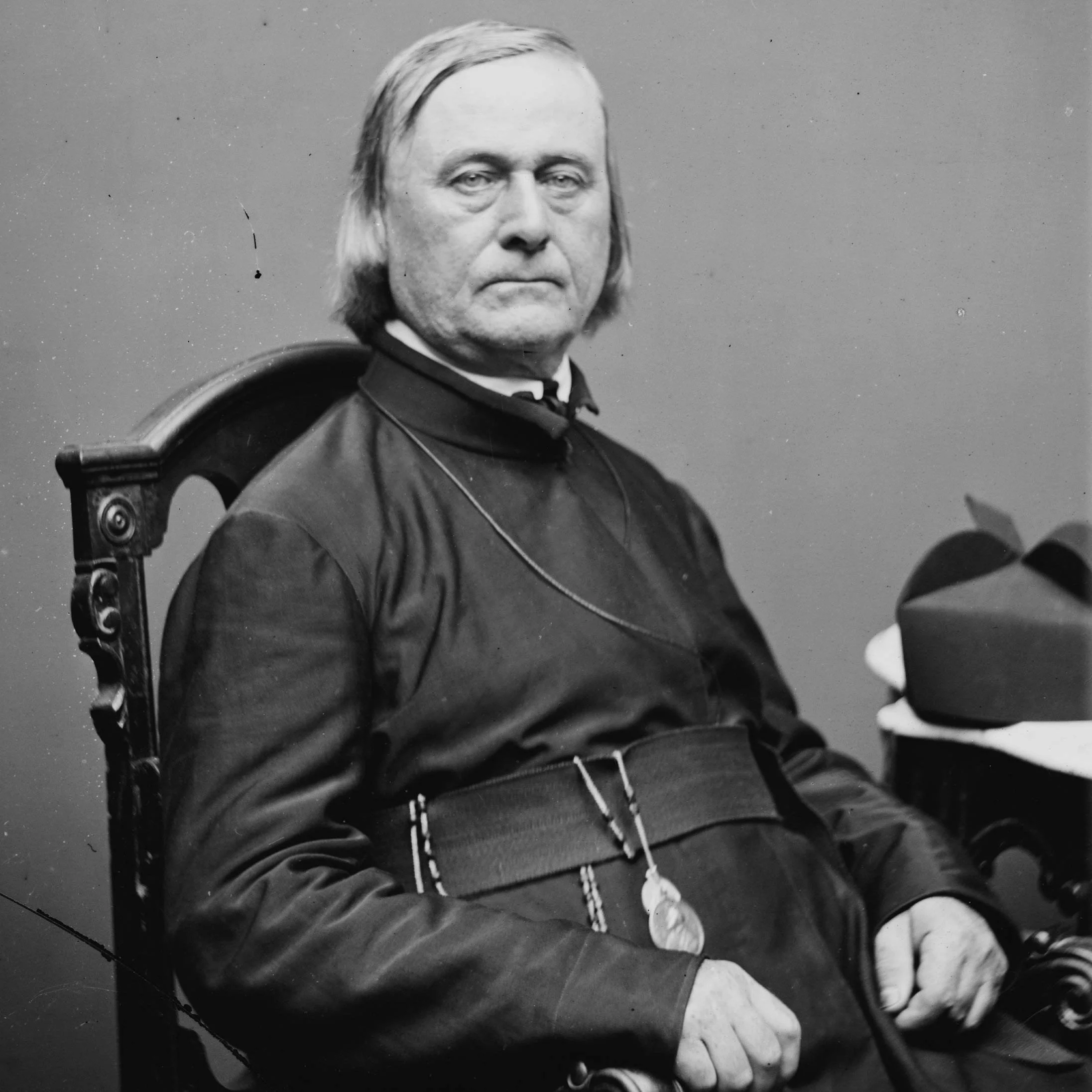

According to H.W. Brands’ The Last Campaign, William T. Sherman, Commanding General of the U.S. Army, asked Gen. Philip Sheridan, who commanded all U.S. Army troops in the West, what he knew about gold in the Black Hills. In a letter to Sherman, Sheridan passed along a tale he’d picked up from Father De Smet, a Jesuit priest and missionary who traveled throughout the northwest United States. While Sheridan and De Smet were on the Columbia River in Oregon a few years earlier, De Smet told the general he’d been shown nuggets of gold from the Black Hills by the Sioux when he once lived with them. They told him they knew where a mountain of it could be found.

The mountain, Sheridan continued, turned out to be a pile of mica the Indians believed was gold. However, the De Smet story did not die. Three years later, Sheridan was in New York and was asked by a “prominent gentleman” how De Smet could be located so someone could discover the mountain of gold “and pay the national debt.”

General Philip Sheridan. (Credit: Library of Congress)

“After I informed him it was an old and exploded story,” Sheridan said of the man, “his ardor cooled and the excitement about the mountain of gold again subsided.”

The lust for gold never subsided and the severe depression that followed the financial crisis of 1873 put millions out of work and gave them time to dream and scheme about the next big gold strike out West.

Prospectors “infiltrated the Black Hills,” Brands writes, despite it being reserved for the Lakotas. The Grant administration declared trespassers would be removed and prosecuted. It failed to dampen the excitement. That was the reason for Custer’s 1874 expedition – to determine if gold was sitting in the Black Hills.

Miners in Custer’s party found gold in July 1874, but no more than could be found elsewhere in the West. Yet the boosters of business in the Dakotas wanted to tout the discovery of gold. They were financially stressed after construction of a planned railroad line in the region was halted due to the economic depression.

The territorial newspaper in Bismarck estimated a man with a pan could make $20 a day finding gold in “Custer’s Gulch.” Sluice mining would return over $100 per day, while profits of hydraulic mining “would be something enormous.”

Rev. Father Pierre Jean De Smet (1801-1873.) (Credit: Library of Congress)

Sheridan, who dismissed “the El Dorado” talk of newspapermen, told Sherman:

“Although I have the utmost confidence in the statements of General Custer and General Forsyth of my staff that gold has been found near Harney’s Peak, I may safely say that there has not been any fair test yet made to determine its existence in large quantities. There is not a territory in the West where gold does not exist. But in many of them the quantity is limited to the color, which is as much as has yet been obtained near Harney’s Peak. The geological specimens brought back by the Custer Expedition are not favorable indications of the existence of gold in great quantities.”

Sheridan allowed Custer may have looked in the wrong place. He thought if there was gold, it was to be found to the west of the Black Hills, maybe in the Wind River range of present-day Wyoming or near the Powder River in present-day Montana.

Sherman publicly emphasized the slight nature of Custer’s find.

“It was very thin,” he told a reporter who asked about Custer’s gold. “Why, these fellows can’t make any money there. In the first place, it would be so far from markets that food will cost them a dollar a pound. It will be just as it was in the earlier mining days in California. (Sherman was in California from January 1847 to 1850.) A man might dig 16 dollars a day, but his meals cost him three dollars a piece or nine dollars a day. And everything else in proportion, so he never made a cent. It will be just so again. And though there may be, as I have no doubt there is gold in those hills, it is comparatively inaccessible to the expense intendent on digging it out.”

Sherman acknowledged that efforts to keep prospectors out of the Black Hills might be contributing to their desire to get in.

“It’s the same old story. The story of Adam and Eve and the forbidden fruit. These people know they have no right there. They know the government prohibits any trenching on the ground. And so they have made up their minds to go there.”

Sherman reiterated Grant’s warning that the Army would use force to prevent trespassing. Yet, he conceded that he lacked the troops required to cordon off the Black Hills completely. He expected trouble with the Lakotas when the gold hunters broke through.

“Of course, there will be a great deal of scalping,” he said.

Sherman compared miners trespassing on Sioux land in the Black Hills to a burglar breaking into a house, and felt the Sioux were within their rights to protect their possessions. If the gold hunters were killed, Sherman said, “they would only have themselves to blame.”