DEC 14: White America’s Policy Toward Indians

Editor’s note: We recently recounted the events of the Battle of Washita, where, on Nov. 27, 1868, Lt. Colonel George A. Custer led a cavalry charge at dawn against a village of Cheyenne camped for the winter in present-day Oklahoma. It was Custer’s first big battle with Indians and it demonstrated his aggressive, reckless attack style. It also demonstrated his willingness to kill men, women and children in order to appease his superior officers, most notably Maj. General Philip Sheridan and Lt. General William T. Sherman.

At the time, Sherman was the commanding officer of the Military Division of the Missouri, placing him in charge of all U.S. Army forces west of the Mississippi River. It was a vast command responsible for the Indian Wars. He was taking heat from Congress for not bringing the Indian problem under control. It was hampering immigrants from moving onto land Congress considered Americans’ rightful territory. The Indians, contrarily, considered it their homeland. During the prior year, Civil War hero General Winfield Scott Hancock led a much-publicized expedition on the Kansas plains intended to bring Indian tribes to heel. It was a complete failure and it led to Sheridan, a mentor to Custer, replacing Hancock and taking over command.

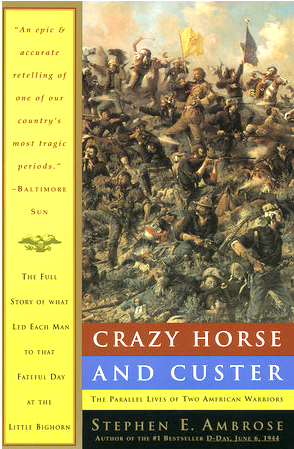

Stephen E. Ambrose.

Sheridan knew Custer from his Civil War exploits as a fighter who could be counted on to get the job done. But, Custer was out of action at the time, having been found guilty in a court martial of deserting his command the previous year in Kansas. The former “boy general” was cooling his heels in Monroe, Michigan, serving his punishment of a year out of the Army. Sheridan got Custer called back to duty in September 1868, and directed Custer to take the fight to the Indians. Custer was eager not only to return to a job he loved, but to redeem himself and do Sheridan’s and Sherman’s bidding by attacking and controlling the Indians.

In his book, “Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors,” author Stephen E. Ambrose points to Custer’s actions at the Battle of Washita as a sample of how the man and the Army leaders he served both exemplified white America’s policy toward Indians.

To recap, Custer and 700-plus cavalry troopers attacked a supposedly peaceful village of Cheyenne under Black Kettle next to the Washita River. The troops, according to Ambrose, released months of pent-up frustration from hardship by slaughtering men, women and children. Dozens of women and children were killed while hiding in their tents or attempting to run away from the camp. Custer then followed the example set previously by Hancock and ordered the village burned to the ground. He also ordered troopers to gun down most of a herd of 900 ponies. It was comparable to “total war” tactics Sherman used during his “March to the Sea” in Georgia and South Carolina near the end of the Civil War.

Ambrose writes:

“It was absolutely within the spirit and letter of Sheridan’s ‘s orders. It was also within the tradition of the American culture and its consistent policy towards Indians. These Cheyennes were enemies of progress. They stood in the way of the settlement of Kansas and they had to be removed.

“Custer’s destruction of Black Kettle’s people and village on the Washita can stand as a symbol of American Indian policy. From the time of the first landings at Jamestown, the game went something like this: you pushed them, you shoved them, you ruined their hunting grounds. You demanded more of their territory until they strike back, often without immediate provocation so that you can say they started it. Then you send in the Army to beat a few of them down as an example to the rest. It was regrettable that blood had to be shed, but what could you do with a bunch of savages?

“The men of the 18th and 19th centuries took it for granted that the Indians had to be Christianized and modernized. But, how could you do that until you caught them? The problem was more difficult on the Plains than it had been in the Eastern woodlands. Because with all that space, it was hard to catch them. Compounding that problem, each Indian on the Plains required vast amount of land to feed himself. To accommodate a few thousand Cheyennes on a reservation that would allow them to live as they wanted to live, the government would have had to have left them in possession of half of Kansas. In an America on an economic boom unprecedented in history, not to mention an America that’s receiving millions of immigrants from Europe, who could abide that loss?

“The point is that for all of America’s leaders’ concerns for the fate of the Indians, they had a higher loyalty. The men who made national policy from the 18th century onward, supported by a broad consensus by the white population, have had as their first loyalty the doctrine of material progress. They believed in that doctrine more than in their constitution or their treaties or their religion. America’s leaders and America’s white population have allowed nothing to stand in the path of progress. Not a tree, not a desert, not a river. Nothing. Most certainly not Indians, regrettable as it may have been to destroy such noble and romantic people. Well, it was regrettable, but who is to say they were wrong? Who can possibly judge? Who would be willing to tell the European immigrant that he can’t go to the Montana mines or the Kansas prairie because the Indians need the land. So, he had best go back to Prague or Dublin. Who wants to tell a hungry world that the United States cannot export wheat because the Cheyennes hold half of Kansas? The Sioux hold the Dakotas, and so on.

“Despite the hundreds of books by Indian lovers denouncing the government and making whites ashamed of their ancestors, and despite the equally prolific literary effort on the part of the defenders of the Army, here, if anywhere, is a case where it is impossible to tell right from wrong. But we can tell truth from falsehood. It is, for example, totally irresponsible to state, as has so often been stated, that the United States pursued a policy of genocide toward the Indians, to cite the Washita as an example. And, in the most extreme statements, to claim that the Army actually did exterminate the red men. The United States did not follow a policy of genocide. It did try to find a just solution to the Indian problem. The consistent idea was to civilize the Indians, incorporate them into community, make them part of the melting pot, that it did not work, that it was foolish, conceited, even criminal, may be true. But that doesn’t turn a well-meant program into genocide. Certainly not genocide as we have known it in the 20th century.

“Custer was many things, but he was no Nazi SS guard shooting down innocent people at every opportunity.”

Post-note: Stephen E. Ambrose was an American historian, academic and author. His books include “Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West” (1996), “Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors” (1975), and “Band of Brothers” (1992). Ambrose, who won an Emmy Award for Band of Brothers, died in 2002 at the age of 66.