OCT 17: Relocating in Texas

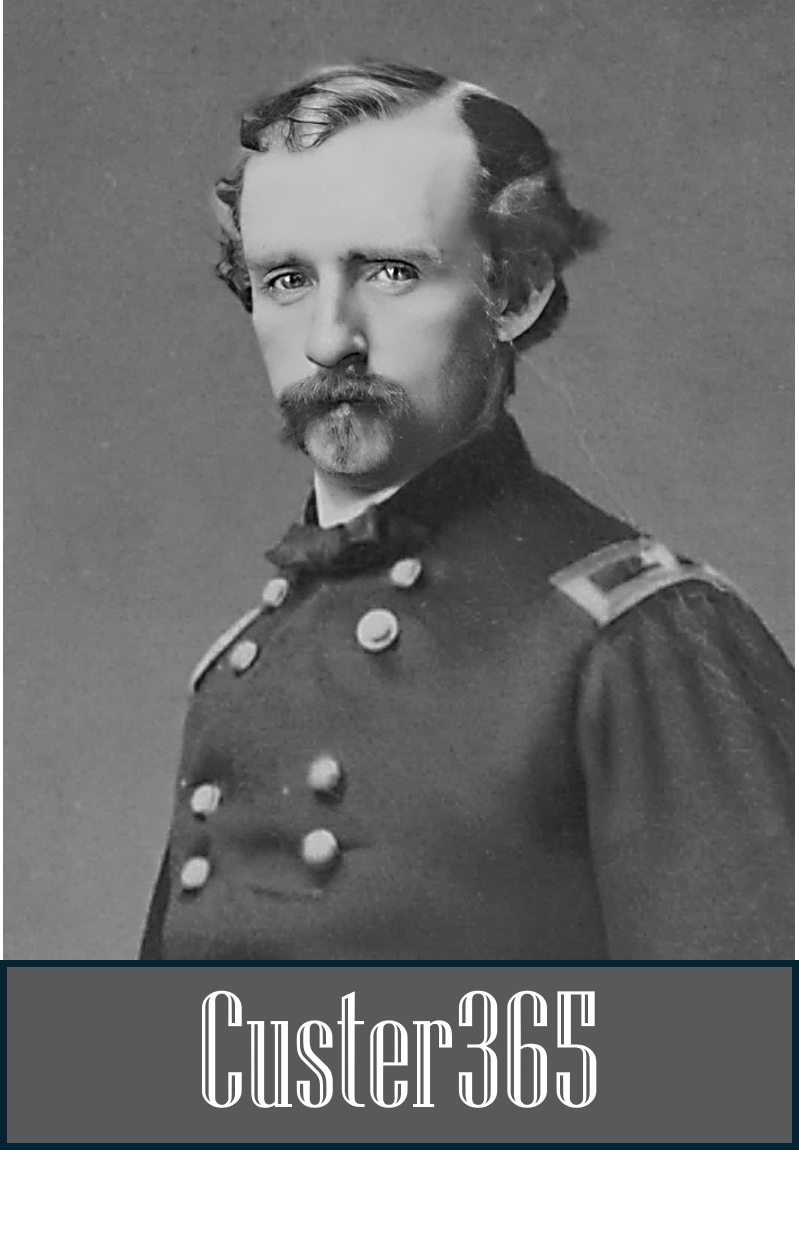

In October 1865, Major General George A. Custer and his cavalry division moved from Hempstead, Texas, to Austin. Custer retained his rank in the Volunteers and was the highest-ranking Army officer in the state of Texas.

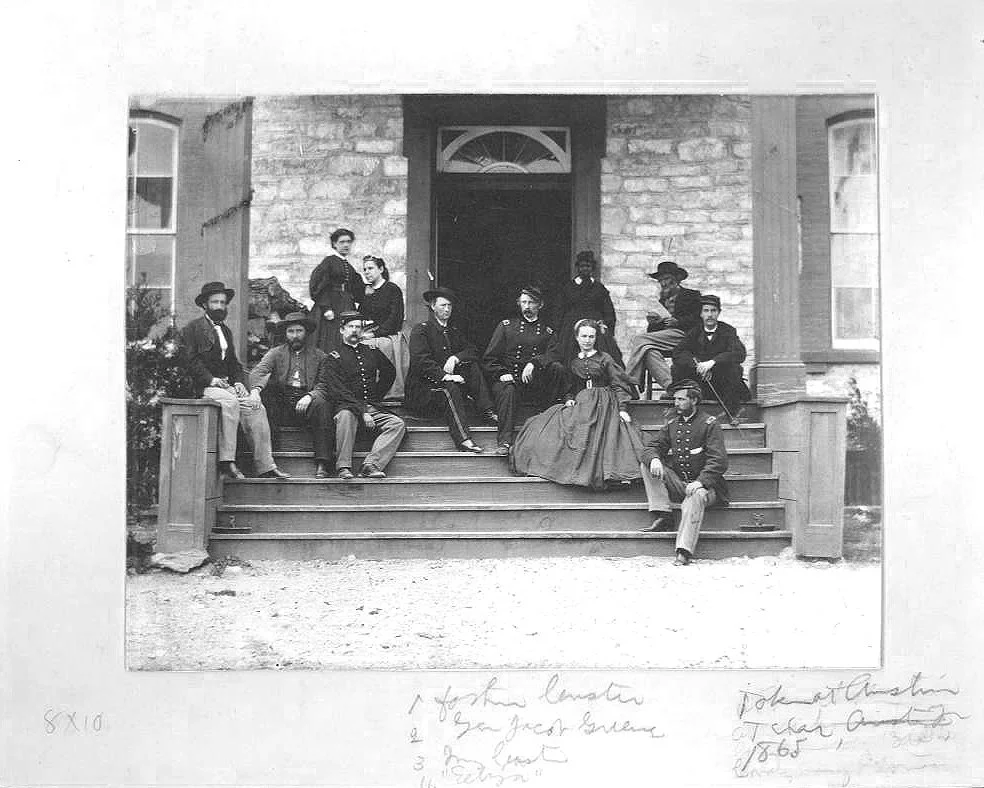

Pictured in this photo taken of the steps of Custer’s Austin headquarters are Col. Tom Custer (center, left), Maj. Gen. George A. Custer (center), Elizabeth Custer, the Custer’s cook Eliza (standing at door), and father Emanuel Custer (seated to the right in wide-brim hat.) (Credit: National Park Service)

He’d originally been sent to Texas from Louisiana to maintain order during post-Civil War Reconstruction and to keep an eye on Mexico, where Emperor Maximilian posed a threat of possible invasion.

During his time in Texas, Custer was surrounded by a coterie of family and friends, including his brother Tom Custer and his father, Emanuel, who had been hired as a forager. In his book, “Custer and Crazy Horse,” author Stephen E. Ambrose described the scene:

“Tom, George Yates and the other Custer hangers-on… went on late afternoon hunting parties, attended dances, played jokes on each other, and generally did their best to enjoy the situation. A mere 25 years of age, he’d been given an assignment that would have taxed the statesmanship of a Lincoln. As senior military officer in Texas, he was expected to see to it that the freed men and women received fair treatment, that unsubdued Rebels behaved themselves, that the rowdy frontiersmen obeyed the government, that the conquered Rebels were punished, and that his own troops refrained from individual acts of lawlessness directed against the people they had so recently conquered.”

Custer’s worst problems, according to Ambrose, were with his own troops. “The men in the cavalry division were westerners, unused to the heavy discipline of the Army of the Potomac. In addition, they wanted to go home, not serve in an occupation duty in Texas.”

Custer had to deal with a serious incident involving the Second Wisconsin Cavalry.

Custer on horseback near Brenham, Texas, in 1865 with Mrs. Carrie Farnham Lyon. (Credit: National Park Service)

“A mob of enlisted men with the help of several of their junior officers attacked the regimental commander demanding his resignation or his life, “ Ambrose wrote. “Custer put an end to the mutiny by arresting 16 of the officers and reduced 76 non-commissioned officers to the ranks.”

Another problem was with troops who assailed civilians, damaged their houses, insulted their women, “and, in general, stole everything not nailed down.” Custer adopted drastic measures “to bring these marauders into line, including this order: Every enlisted man committing depredations on the persons or property of citizens will have his head shaved and, in addition, will receive 25 lashes on his back well laid on.”

Desertion was another major concern during Custer’s time in Texas.

“Civil War volunteers were no more anxious to sweat in Texas than they were to fight Crazy Horse in Wyoming, and they deserted in droves,” according to Ambrose. “Custer had at least one deserter shot and although it evidently lowered the desertion rate, the action got him into further trouble, as reported in the northern press. Here was Custer hob-knobbing with former Rebels, engaging in horse races and trads with former Confederate generals, enjoying the supposed luxuries of Southern plantation living and, meanwhile, flogging or shooting the brave boys who had saved the Union.”