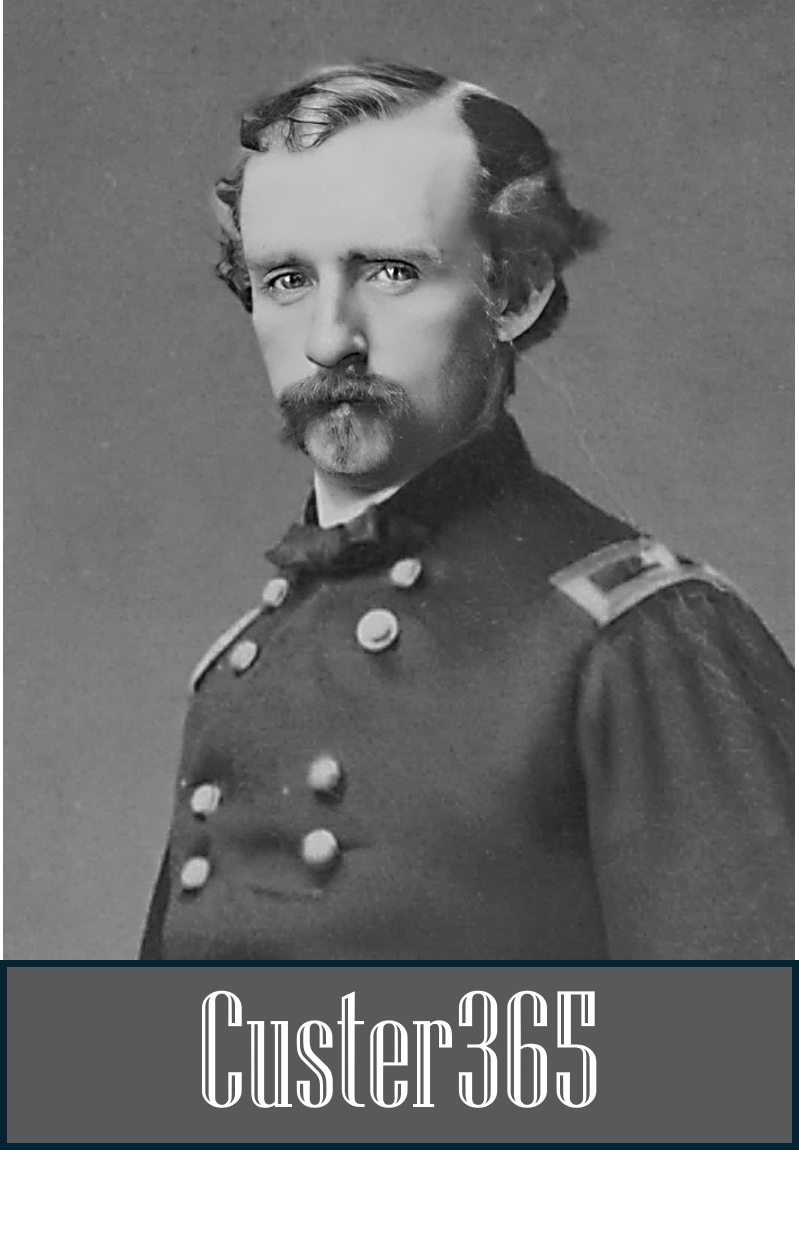

OCT 6: ‘Custer Luck,’ Episode One

Several authors have pointed out George Armstrong Custer’s uncanny streak of good fortune, whether it was having a dozen horses shot out from under him during the Civil War and escaping with his life, or having military connections pay off with timely promotions. During Custer’s time, it became known as “Custer Luck.”

In his 1975 book, “Custer and Crazy Horse: The parallel lives of two American warriors,” author Stephen E. Ambrose wrote, “his Civil War record is replete with incidents in which he was at the right place at the right time.”

Winfield Scott, hero of the Battle of Vera Cruz in 1847. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Case in point: Shortly after he and his class at West Point graduated one year early in June 1861, Custer remained behind while classmates rushed to Washington, D.C. for new assignments in the U.S. Army. Custer did not join them because he had been court-martialed for failing to stop a fight between cadets while he was on guard duty.

Ambrose writes: “When Custer left West Point to take up his duties in Washington, for example, his classmates had a two week jump on him. They had been where the action was while he had sat in the guard house at West Point. On the train to Washington, Custer had probably fretted that his friends had taken all the choice assignments and that he would get off to a poor start in his Army career.

“He arrived in Washington on the eve of the first battle of Bull Run. In reporting to the Adjutant General’s office, he had to wait a few hours in order to find an officer with time enough to accept his papers. The officer glanced at them, looked at some records, and informed Custer that he had been assigned to the Second Cavalry. Then, almost as an after-thought, the officer casually inquired, “Perhaps you would like to be presented to General Scott, Mister Custer?’

Brig. General Irvin McDowell. (Credit: Library of Congress)

“Then… young Armstrong stood dumbfounded. He had glanced at the figure of Winfield Scott when that dignitary visited the Academy for reviews, but the General had been as untouchable as the upper social set back in Monroe (Michigan.) He stammered assent. Winfield Scott, an old man by this time and soon to be retired made something of pets of the West Point cadets and was always willing to do something special for them. After an exchange of greetings, Scott told Custer that his classmates were drilling recruits. ‘Now, what can I do for you? Would you prefer to be ordered to General Mansfield to aid in this work or is your desire for something more active?’ What a choice. Custer indicated that he wanted to go into the line. ‘A very commendable resolution, young man,’ Scott replied. ‘Go and provide yourself with a horse, if possible, and call here at 7 o’clock this evening. I desire to send some dispatches to General McDowell at Centreville and you can be the bearer of them. You are not afraid of a night ride, are you?’ Brigadier General Irvin McDowell was in command of the Union troops in northeastern Virginia. ‘No sir,’ Custer replied, snapping into a salute.

“His luck continued to hold. He found a horse by great good fortune, made the ride to McDowell’s headquarters, handed over Scott’s dispatches, got to meet McDowell’s chief staff officers, joined his regiment, participated in the Battle of Bull Run, got himself mentioned in the reports on the engagement, and had a quiet laugh at his classmates who had missed the battle.

“And it all happened because he had been court-martialed at West Point and was, thus, late in reporting for duty.”