SEPT 6: Ely S. Parker is Mourned

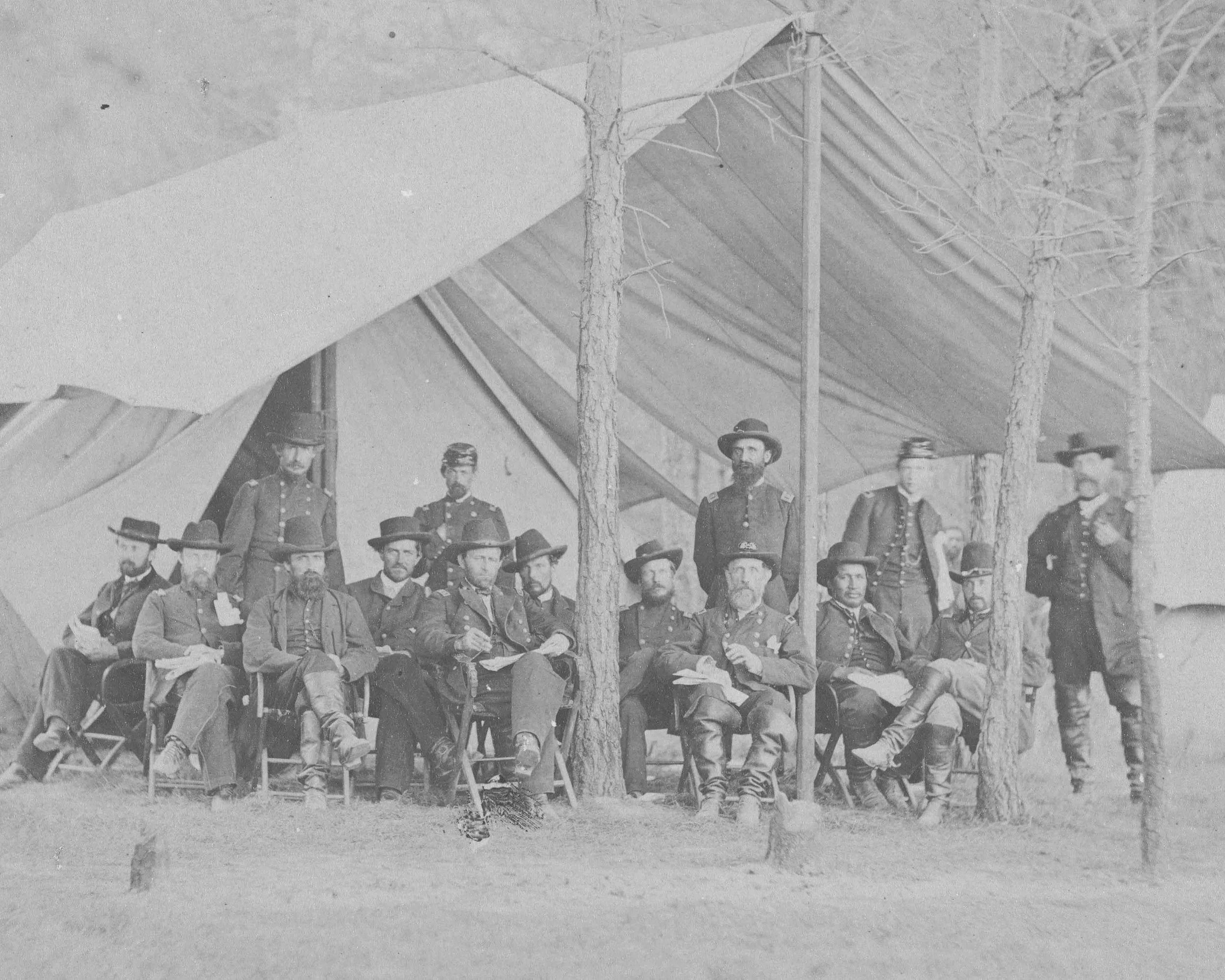

General U.S. Grant (seated fifth from left) and Col. Ely S. Parker (seated second from right) at Grant’s headquarters at Cold Harbor, Va., 1864. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Friends of Ely Samuel Parker, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1869-1871) under President Ulysses S. Grant, continue to mourn his death this week in 1895 in Fairfield, Connecticut. He was 67.

Born as Donehogawa (Keeper of the Western Door of the Long House of the Iriquois), his name as a youngster on the Tonawanda reservation was Hasanowanda of the Seneca Iriquois tribe. In his book, “Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee,” author Dee Brown wrote, “Hasanowanda changed his name to (Ely) Parker because he was ambitious and expected to be taken seriously as a man.”

Parker worked as a stable boy on Army post and was teased by soldiers because of his poor English. He attended missionary school to learn how to speak and write English, and he aspired to become a lawyer. He worked for three years at a law firm in Ellicott, New York, but when he went to take the bar exam, “he was told only white citizens could be admitted to a law practice in New York. No Indians need apply,” Brown wrote. Parker then studied which industries would accept an Indian and found that Engineering was one of them.

Parker entered Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY, and studied civil engineering. He soon was employed on the Erie Canal and before he turned age 30, the U.S. government had him supervising construction of levees and buildings. In 1860, Parker’s work took him to Galena, Illinois, where he met and made friends with a former Army captain working in a harness store. His name was Ulysses S. Grant.

When the Civil War broke out, Parker returned to New York to raise a regiment of Iroquois Indians to fight for the Union. He was turned down by the government and was told there was no place for Indians in the New York Volunteers. Parker traveled to Washington, D.C., and offered his services as an engineer to the War Department. While they needed trained engineers, they didn’t need Indian engineers, according to Brown.

Parker returned to the Tonawanda reservation, but let his friend Grant know he was having difficulty entering the Union Army. Grant needed engineers “and after battling Army red tape for months, he finally managed to have orders sent to his Indian friend, who joined him at Vicksburg,” Brown wrote.

Parker remained with Grant to the end of the war. When Robert E. Lee, General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States, surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865, Colonel Ely Parker drafted the surrender terms. Later, Brigadier General Parker served on missions to settle differences with Indian tribes.

After Grant was elected president in November 1868, he chose Parker to be the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, “believing he could deal more intelligently with Indians than any white man,” according to Brown. Parker was the first Native American to serve in a presidential administration. Parker worked to implement President Grant's “Peace Policy”, which was aimed at replacing military conflict with diplomacy and reducing the influence of a corrupt "Indian Ring" that exploited tribes.

Parker found the agency rife with corruption. A clean sweep of entrenched bureaucrats was in order, so, with Grant’s approval, Parker began selecting new Indian agent replacements from religious organizations with established relationships with tribes. So many Quakers volunteered that the government’s policy on dealing with Indian tribes became known as “the Quaker Policy.”

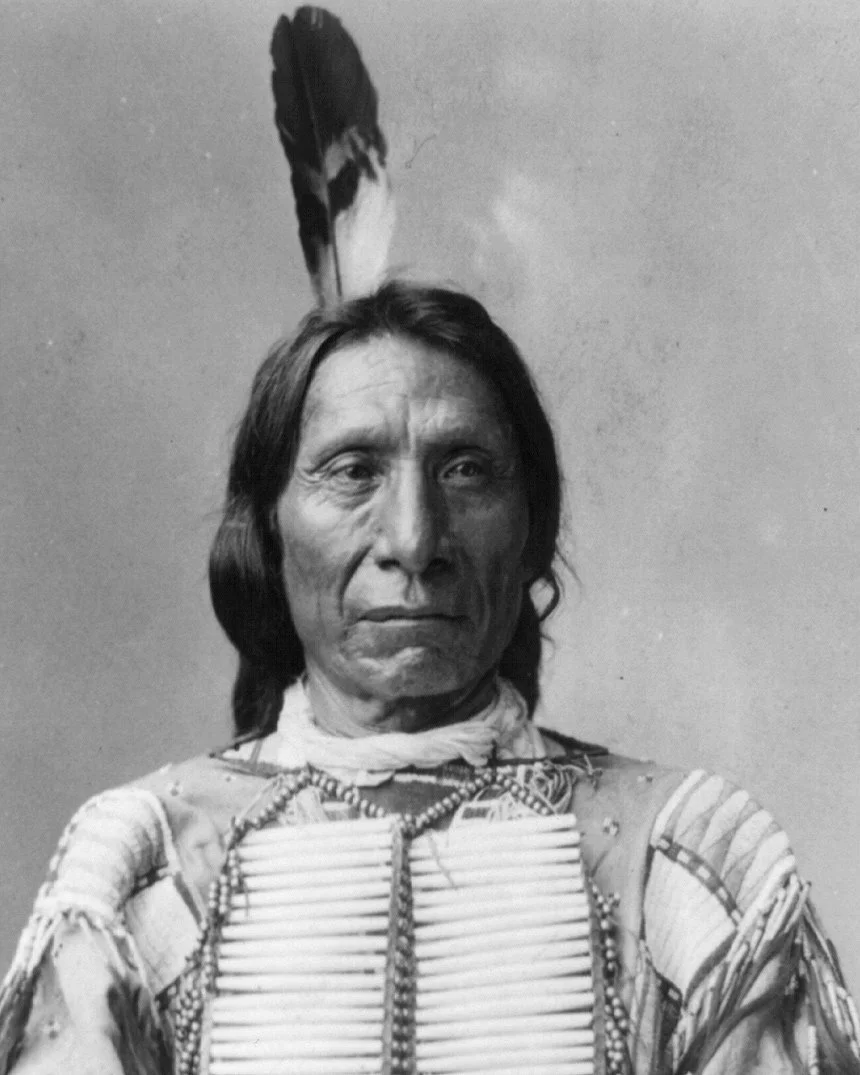

Oglala Chief Red Cloud. (Credit: Library of Congress)

In spring of 1870, reports of a brewing rebellion at agencies on the Plains increased. Red Cloud, chief of the Oglala Sioux, was determined to keep his country in western Nebraska and get the government to place an agency near that land. The government was pressing for several tribes to relocate to an agency quite a distance away along the Missouri River. Red Cloud was invited to come to Washington, D.C. in June and meet with “the Great Father” (Grant). Red Cloud was intrigued and wanted to see if “the Little Father” (Parker) was truly an Indian. The chief brought 15 additional Oglalas with him.

Parker took them on tour of Congress in session and the Navy Yard. Matthew Brady invited them to his studio to have their photos taken. Red Cloud, at first, said he wasn’t dressed properly (they were given suits of clothes to wear) and didn’t want to participate. Parker told Red Cloud and the others to wear their buckskins to dinner with Grant, if they desired.

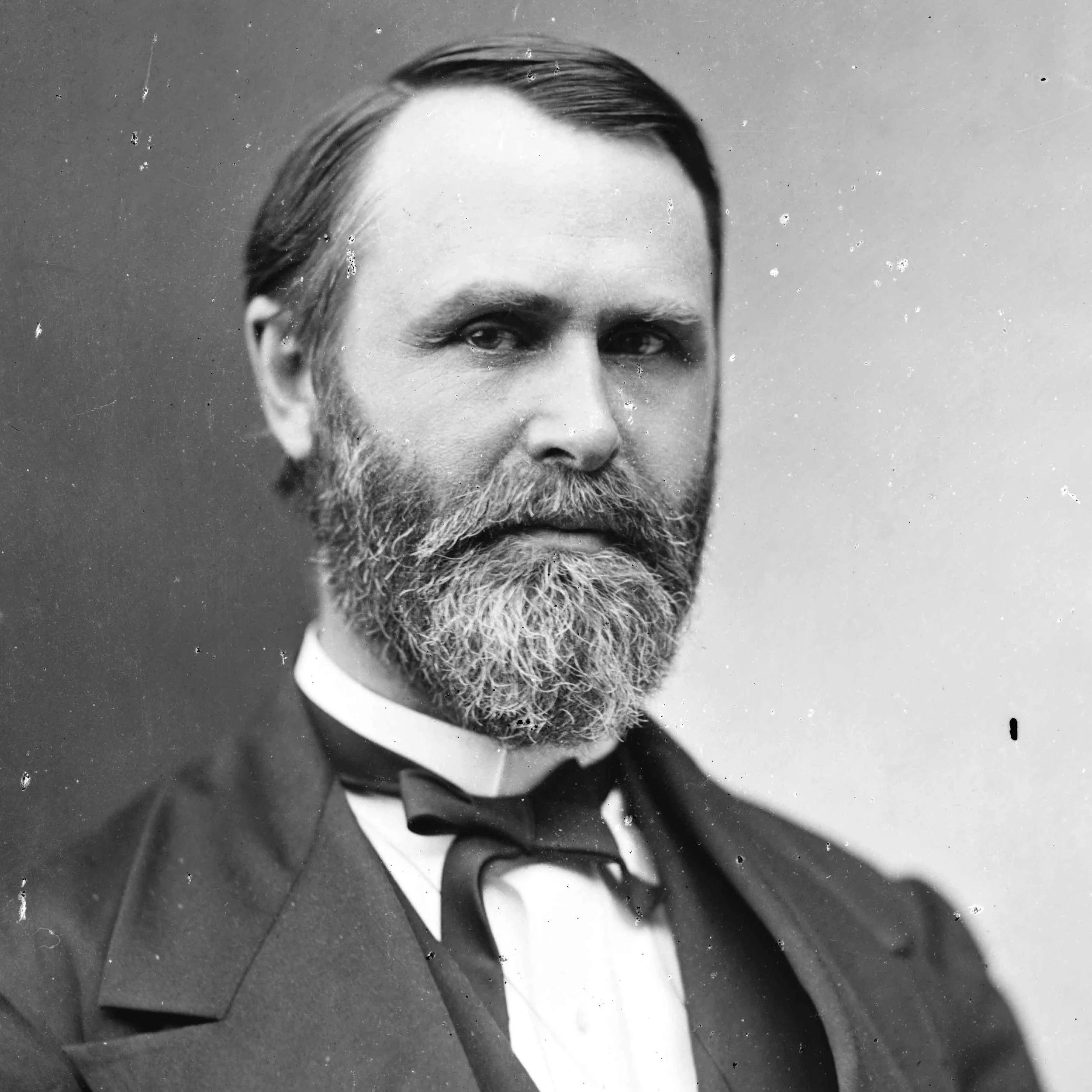

Secretary of the Interior Jacob D. Cox. (Credit: Library of Congress)

During a meeting between Interior Secretary Jacob D. Cox, Parker, and Red Cloud, an interpreter read aloud the terms of the 1868 Laramie Treaty, which Red Cloud had signed. The chief became indignant and said it was not the treaty he’d agreed to two years earlier. The government, once again, had lied and cheated him. Parker and Cox hurriedly met with President Grant, who told them to thoroughly explain the points of the treaty again to Red Cloud. This time with a slightly altered interpretation, promoted by Parker, Cox told Red Cloud he could live on his hunting grounds and not the reservation designated for him, if he wished. Red Cloud agreed.

Parker had enemies in Congress, including interests in the “Indian Ring” that was part of the lucrative government spoils system. In the summer of 1870, Congress withheld funds for food and other supplies for Indian reservations. Hearing from Indian agents that an uprising was imminent, according to Brown, Parker went outside the system and purchased supplies on credit, then, without bids, shipped goods to the reservations at higher rates than normal. The regulations Parker broke were minor, but his enemies in Congress claimed he’d committed fraud. Parker was called before a House committee and grilled for days. One witness claimed that Parker’s tolerance of Native American religious practices made Parker a “heathen commissioner.” After being exonerated of wrong-doing, Parker remained in office, yet agonized over wanting to continue to advance his race, but not at the expense of Grant’s political fortunes. Parker eventually resigned in summer 1871.

He left Washington, D.C., moved to New York and made a fortune in finance, according to Brown. He died on Aug. 31, 1895, at the age of 67 and was buried with full military honors.