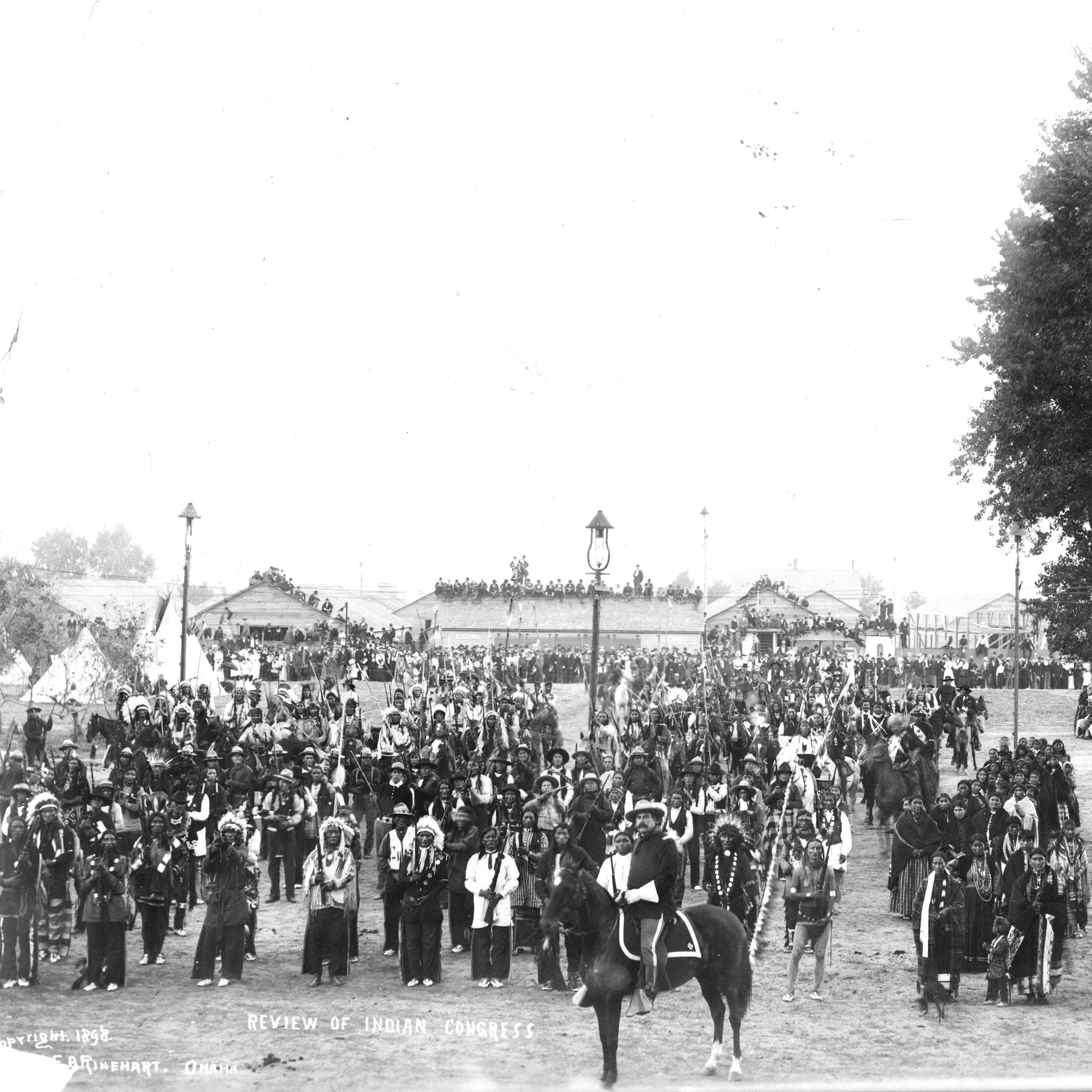

AUG 13: Indian Congress in Omaha

A review of the 1898 Indian Congress in Omaha, Neb. (Credit: Library of Congress)

On Aug. 13, 1898, the Indian Congress continues its three-month run at the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Omaha, Neb.

Years later, it was spun as a “notable moment in Native American history, showcasing both the pressures of assimilation and the enduring resilience of indigenous cultures.” At the time, the Congress was held within a decade of the Massacre at Wounded Knee and the end of the Indian Wars.

It was the dream of ethnologist James Mooney to re-create the Indian way of life of a bygone era, which was, in reality, a time when most whites despised everything Indian and, eventually, destroyed them and their respective cultures.

It was the largest gathering of American Indian tribes of its kind to that date. More than 500 members of 35 different tribes attended, including the Apache war leader and medicine man Geronimo, who was being held at Fort Sill in Oklahoma Territory at the time as a prisoner of the U.S. government.

The Indian Congress was managed by Mooney, who worked for the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) for more than 30 years, and Army Capt. William Mercer of the 8th U.S. Infantry. Work was conducted under the direction of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs acting on behalf of Cornelius Newton Bliss, the Secretary of the Interior.

The original intention of the organizing committee was to illustrate the daily life, industry and traits of as many tribes as possible. (Author’s note: Traits that the U.S. Army, on behalf of the federal government, wiped out in little more than 70 years.) However, once the Congress was open authorities realized that a glimpse into the daily lives of American Indians wasn’t drawing crowds. Fair-goers wanted to see dances, games, races, ceremonials and replicated battle scenes.

Promoters erected a 5,000-seat grandstand and arranged the tribes in battle re-enactments. They also re-enacted the Ghost Dance, which was a late 19th century religious movement among Native Americans, particularly those on the Plains, that emerged in response to hardships suffered on reservations and a decline of traditional ways. It involved a specific dance ritual that many believed would hasten the return of deceased ancestors, restore the buffalo to the plains, and remove white settlers.

Apache medicine man Geronimo. (Credit: Library of Congress)

The Ghost Dance craze, coupled with hatred of Indians by white soldiers seeking to avenge the deaths of George Custer and the 7th Cavalry at Little Bighorn, led to the Wounded Knee Massacre on Dec. 29, 1890, in present-day South Dakota. There, an estimated 300 Lakota Sioux were killed, including women, children and the elderly. The event is considered the end point of the Plains Indian Wars.

Mooney contracted with photographers Frank A. Rinehart and Adolph Muhr to take photographs of the attendees. Rinehart made several hundred pictures, regarded as one of the most complete collections of Native American portraits in existence.

The tribes in attendance included: the Apache, Arapaho, Assiniboines, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Chippewa, Crow, Flathead, Fox, Iowa, Kiowa, Omaha, Otoe, Ponca, Pottawatomie, Santa Clara Pueblo, Sauk and Fox, Lakota, Southern Arapaho, Tonkawa, Wichita, and Winnebago.

Sioux Chief Hollow Horn Bear. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Indian Congresses were also convened at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901 and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904.

To view examples of the Rinehart / Muhr photos from 1898 Indian Congress on the Library of Congress’ website, click the link: