AUG 25: Book Review 2 - ‘Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee’

PART ONE

If you’re looking for a book about how the United States made, then broke, then made, then broke treaties again and again with Native American tribes during the 19th century, then Dee Brown’s “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West” is a one-stop-shop on the subject.

First published in 1971, “Bury,” as one review described it, “took a sledgehammer to the narrative of how the American West was won.” CBC Books described it as a “classic, eloquent, meticulously documented account of the systematic destruction of the American Indian during the second half of the nineteenth century.”

Brown’s book lays out in glaring detail multiple efforts by the U.S. government to entice, cajole, and then force Indian tribes off their lands throughout the West in order to ease the entry of the telegraph, transcontinental railroad, westward emigrants and gold seekers.

In most cases, the native tribes had little understanding of why the government was ignoring the fact that these tribes had occupied and, implicitly, was theirs. Tribes didn’t offer to purchase land from one another. That was a white man’s practice.

The whites cut roads through Indian lands. They laid tracks through their lands (multiple railroad lines.) And, possibly the most-glaring lapse, was the government’s disregard of the Laramie Treaty of 1868, which committed the United States to closing the Bozeman Trail and abandoning forts that protected travelers along the route from Fort Laramie into Montana. The treaty also established the Great Sioux Reservation in the Black Hills, sacred to American Indians, and set it aside for exclusive use of the Sioux people. Custer’s Expedition of 1874 into the Black Hills discovered only a minute trace of gold, but acknowledgement by the government that gold existed triggered a stampede of gold miners that the government couldn’t stop or refused to stop.

Brown covers white Europe’s first encounter with native people of North America. In 1492, Christopher Columbus found the Tainos of San Salvador to be “peaceable” people. Later, entire villages in the islands were burned to the ground and their inhabitants were kidnapped and sold into slavery in Europe.

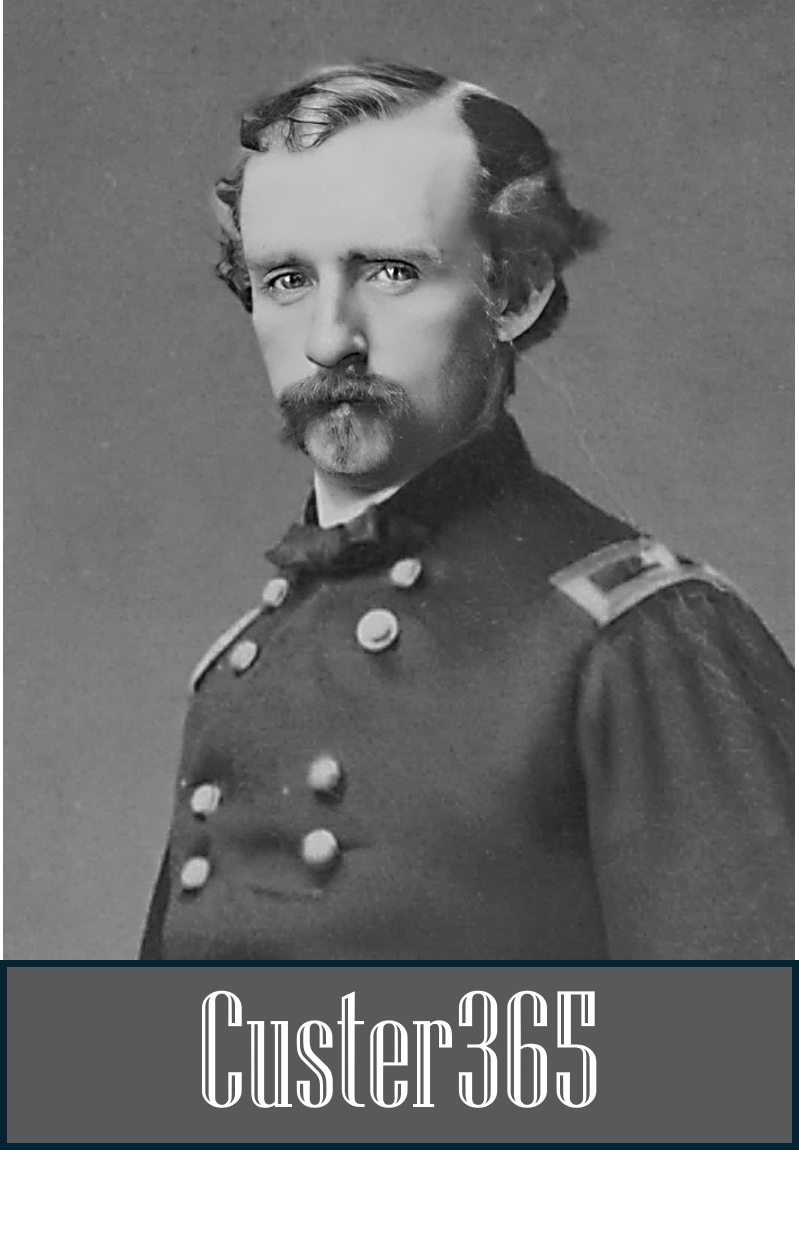

The U.S. government and U.S. Army weren’t alone in efforts to either move native tribes off their lands and onto government reservations. Colorado took justice into its own hands, namely those of Col. John Chivington and his Colorado volunteers. They wanted to clear the state of Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes so miners would have an easier time searching for gold after the Pike’s Peak gold rush of 1858. Chivington’s aim was to “Kill Cheyennes whenever and wherever found.” Colorado Governor John Evans signed a proclamation in 1864 authorizing “all citizens of Colorado” to kill any and all “hostile Indians.”

White hatred boiled over on November 29, 1864, when a force of 700 soldiers led by Chivington attacked non-warring Cheyenne camped at Sand Creek. The camp’s warriors were out hunting, so the white solders indiscriminately slaughtered 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children and elderly people.

One challenge the government faced continuously in attempting to secure treaties with tribes, Brown points out, were requirements that a certain number of tribesmen or chiefs were required to sign the documents.

In Summer/Fall 1865, a commission led by Newton Edmonds, governor of Dakota Territory, and Gen. Henry Sibley, who drove the Sioux out of Minnesota, met separately with leaders of tribes living in areas being overrun by a wave of post-Civil War emigrants. The U.S. government wanted to secure rights of passage from the Indians for trails, roads and planned railroads across the country.

Nine treaties were completed by the commission with the Sioux, including the Sioux branches of Brules, Hunkpapas, Oglalas and Miniconjou, but they weren’t signed by most of the warrior chiefs, including the leading chief of the time, Red Cloud. Nonetheless, they were hailed in Washington, D.C. as a sign of the end of Indian hostilities. But, even Edmonds acknowledged they were worthless.

One passage in chapter 7 exemplifies the Army’s typical approach to dealing with tribes that refused to move off their land so white settlers, railroad men and miners could move in and freely take over.

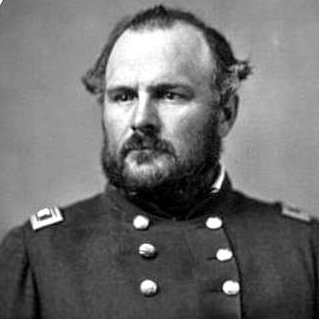

In a meeting at Fort Larned in central Kansas in April 1867, Civil War hero Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, either with great arrogance or unvarnished candor, informed Indian leaders in attendance how things were going to transpire.

Hancock: “I have heard that a great many Indians want to fight. Very well, we are here and are come prepared for war. If you are for peace, you know the conditions. If you are for war, look out for the consequences.”

Hancock then addressed rumors that the railroad was coming out of Fort Riley to the Smoky Hill country:

“The white man is coming so fast that nothing can stop him. Coming from the east and coming from the west like a prairie on fire in the high wind. Nothing can stop him. The reason for it is the whites are a numerous people and are spreading out. They require room and cannot help it. Those on one sea in the west wish to communicate with those living on another sea in the east. And that is the reason they are building these roads. These wagon roads and railroads, and telegraphs. You must not let your young men stop them. You must keep you men off the roads. I have no more to say. I will await the end of your council to see if you want war or peace.”

The next day, Hancock moved 1,400 troops down to a Cheyenne village seeking to speak with influential Cheyenne warrior Roman Nose, who was not at the Fort Larned meeting because he was not a chief and only chiefs were invited.

The Cheyenne, many of whom had family members killed in the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado 2-1/2 years earlier, fled the village. An enraged Hancock ordered his men to burn the village of 900 teepees to the ground.

(END OF PART ONE)

Review: 5 of 5 sabers!

Col. John Chivington. (Credit: Colorado History Museum)

Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Chief Roman Nose. (Credit: New York Public Library)