AUG 26: Book Review 2, Finale

CONTINUED…

Brown provides the perspectives of various tribes throughout the book. Take, for instance, the words of Wamditanka (Big Eagle) of the Santee Sioux:

“The whites were always trying to make the Indians give up their life and live like white men – to farming, work hard and do as they did – and the Indians did not know how to do that, and did not want to anyway… If the Indians had tried to make the whites live like them, the whites would have resisted, and it was the same way with many Indians.”

In subsequent chapters Brown covers:

· Cochise and the Apache guerrillas;

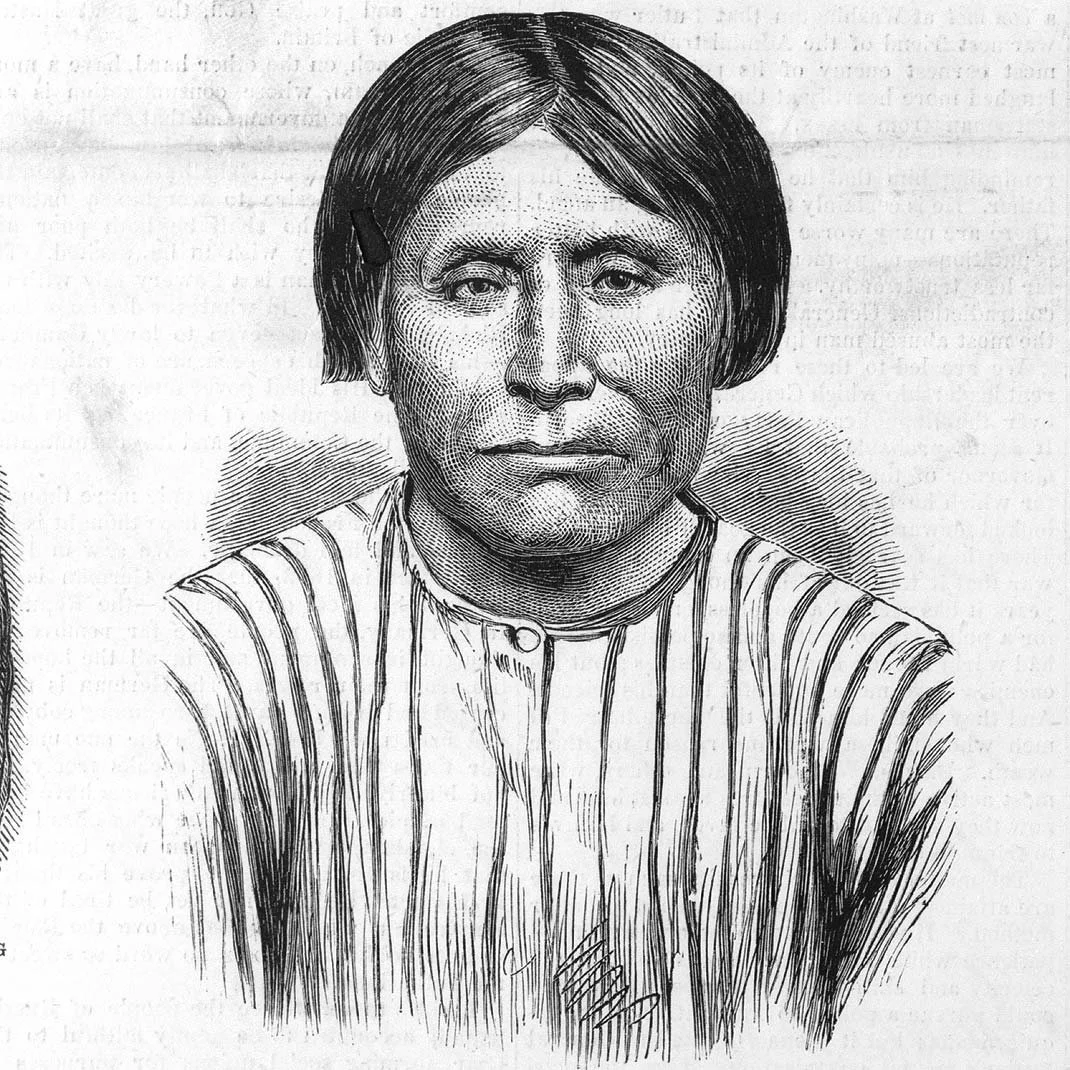

Modoc chief Captain Jack. (Credit: Library of Congress)

· The “ordeal” of Modoc chief Captain Jack in northern California. Captain Jack assassinated General Edward Canby at a peace conference, and was later convicted of the murder and hanged in October 1872;

· The flight of the peaceful Nez Perces after a nearly 20-year effort by the U.S. government to strip them of their lands in Idaho, Oregon and Washington;

· Removal of the Ponca Indians from Nebraska;

· The betrayal of the Utes in Utah and Colorado, after they were promised money and provisions for 10 years as long as they relinquished mineral rights to all parts of their territory.

Brown concludes the book with events in December 1890 that led to the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek in present-day South Dakota. By fall of that year, the Ghost Dance religion had influenced tribes from as far west as Idaho to a small contingent of Miniconjou Sioux living near the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

The Ghost Dance was a spiritual movement founded by an Indian prophet named Wovoka in 1889. It was a ceremonial, nonviolent dance in the round aimed at bringing about the return of traditional native American way of life by ushering in a new earth free of white settlers. It was supported by Lakota Chief Sitting Bull and quickly gained popularity with Indian tribes. It terrified the whites.

Sitting Bull was killed on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in South Dakota on Dec. 15, 1890, following a confrontation with Indian police who were attempting to arrest him in connection with the Ghost Dance movement.

Chief Big Foot.

Chief Big Foot (Spotted Elk) then led a group of the Miniconjou Lakota tribe, along with some members of Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa tribe, from Standing Rock on December 17. He said their new destination was to be the Pine Ridge agency nearby, where legendary Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud lived. He was hoping Red Cloud could protect them from the U.S. Army.

The Army was in pursuit of Big Foot, considered to be a “fomenter of disturbances.” Big Foot became ill with pneumonia enroute to Pine Ridge and had to travel by wagon. On Dec. 28, as they neared Porcupine Creek, Miniconjous sited four troops of U.S. Cavalry approaching. Big Foot met with Major Samuel Whitside, who informed the chief he had orders to take him to a cavalry camp along Wounded Knee Creek.

Rather than disarm Big Foot’s band at that time, Whitside decided to wait until they were at the cavalry camp. With two troops of cavalry leading a column of Indians, two additional troops of cavalry and Hotchkiss guns followed behind. A Hotchkiss gun, with its rifled barrel, could hurl explosive charges for more than two miles.

Troopers counted the Indians: 120 men and 230 women and children. Whitside assigned them a campground and provided food. He also sent a surgeon and camp stove to Big Foot’s tent.

Two troops of cavalry surrounded the Indian tents overnight and two Hotchkiss guns were placed atop a bluff above the campground.

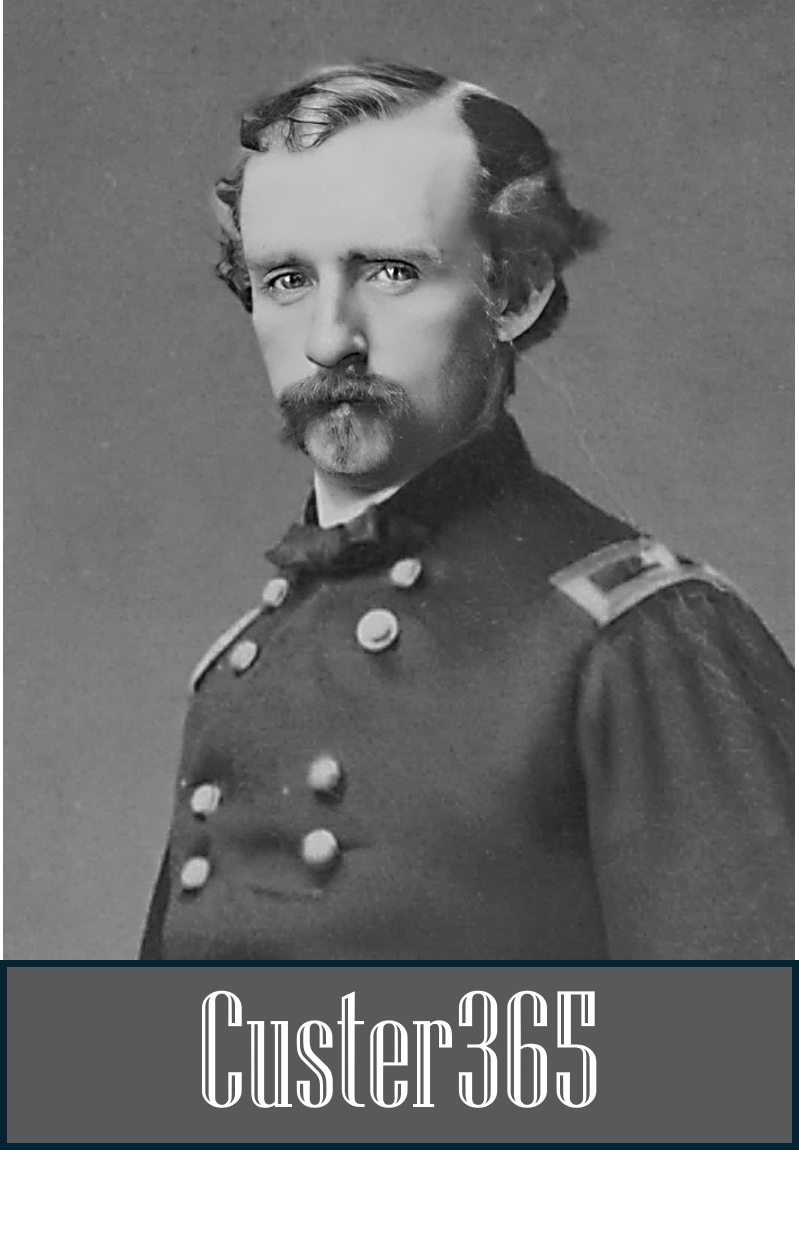

A contingent of the 7th Cavalry, George Custer’s old regiment, showed up under command of Col. James W. Forsyth, who took charge of operations. Forsyth told Whitside he had orders to take Big Foot’s band to a nearby Union Pacific station and then on to a military prison in Omaha.

Two more Hotchkiss guns were place on the slope above the Indian camp. Forsyth and officers then opened keg of whisky to celebrate the capture of Big Foot, according to Brown.

Fourteen years earlier, some of the same Miniconjous in the camp had defeated Custer at Little Bighorn. Some of the “soldier chiefs” at the same camp lost comrades at Little Big Horn. Brown wrote that some Indians “wondered if revenge could still be in their hearts.”

Following bugle call in the morning, soldiers mounted their horses and surrounded the Indians. The Miniconjou men were ordered to come to center of the camp for a talk, then they were told they would move on to Pine Ridge Agency. Big Foot, gravely ill, was brought out to the center. Forsyth called for all guns and arms to be taken from the Indians and stacked up in the center of a circle. The soldiers were not satisfied with the number of guns produced, so details of troopers fanned out to search teepees. They brought back axes, knives and tent stakes and piled them near the guns. Soldiers then ordered Indians to remove their blankets for another search.

A Miniconjou named Black Coyote protested and held up a new Winchester rifle he had recently purchased. Black Coyote was believed to have been deaf. As he held up the gun and was unresponsive to commands from the soldiers, someone grabbed him and spun him around. They grabbed the gun and then, according to a witness, there was the loud report of a gun shot. What followed was the sound of a crash, like the sound of “tearing canvas” or “a lightning crash,” Brown writes.

A photo taken three weeks after the massacre at Wounded Knee in January 1891. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Soldiers then began to indiscriminately shoot Indians with their carbines, filling the air with power smoke. Big Foot lay dead. Then, the Hotchkiss guns opened fire and flying shrapnel shredded teepees and killed men, women and children.

In total, 153 Indians were known dead on the spot. Many of the wounded crawled away to die later. Approximately 300 of 350 Indians at the scene were killed. Of the soldiers, 25 were dead and 39 wounded, most were struck by their own bullets or shrapnel.

The U.S. Army massacre of Black Foot’s Miniconjou Sioux at Wounded Knee was the last major event of the American Indian Wars and symbolized the end of armed Indian resistance to force assimilation and the reservation system.

Wrap-up

5 of 5 saber rating.

Brown’s book is an encompassing look at decades of lies, missteps and deceitful practices perpetrated on American Indians by the U.S. Government and U.S. Army. It’s a vital read for anyone hoping to understand circumstances surrounding the calculated decimation of native Americans in the 19th Century.

It gets five enthusiastic cavalry sabers out of five from the Custer365 review team.